W.Va. Board of Education President Hardesty challenges lawmakers to level playing field for public education

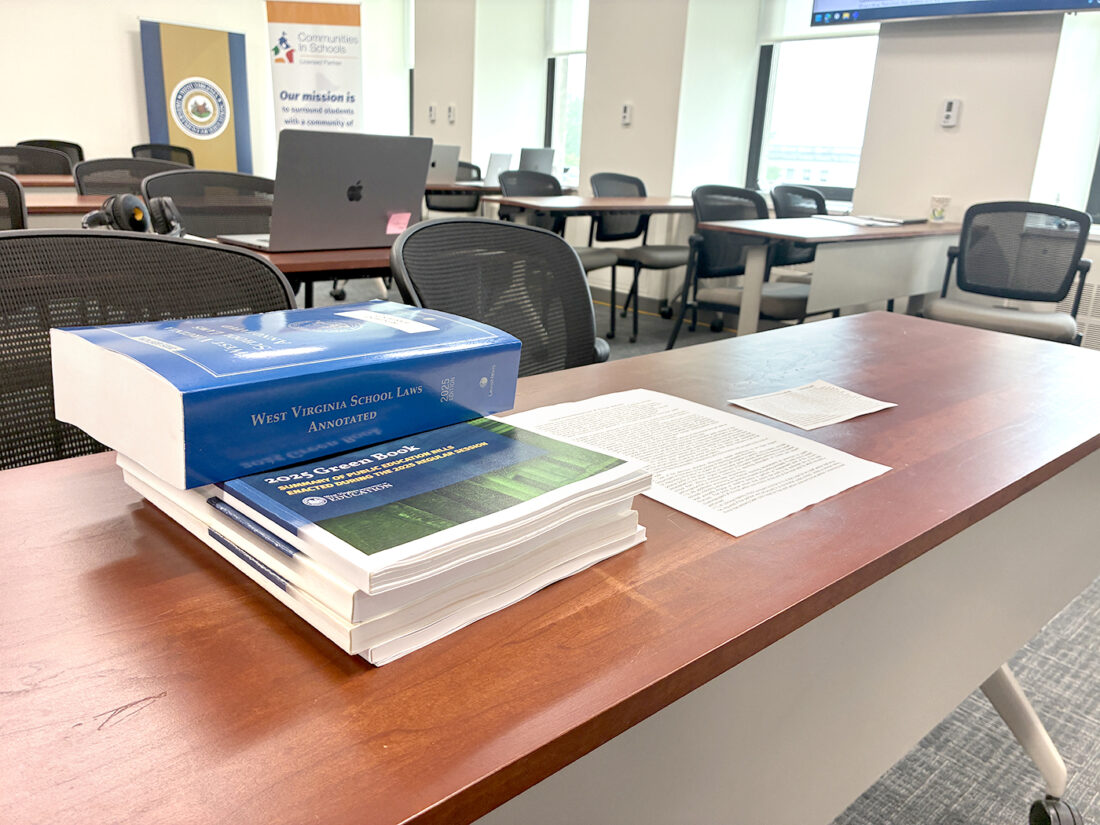

STATE CODE — A display during Wednesday’s West Virginia Board of Education meeting shows what regulations county school systems have to abide by, left, versus the rules the public charter school system abides by, middle, and what regulates home schooling, right. -- Steven Allen Adams

CHARLESTON — Paul Hardesty, the president of the West Virginia Board of Education, has a blunt message for lawmakers: if they care about competition in the education space, then untie the hands of public educators and county school systems.

“We have the best option. Ours is free,” Hardesty said Wednesday morning during the state Board of Education’s regular meeting at the Department of Education offices on the campus of the State Capitol Complex. “We try every day to make it more competitive. But you’ve got to level the playing field. This assault on public education…has got to stop.”

Article 12 of the West Virginia Constitution places the general supervision of the state’s 55 county school systems in the hands of the nine-member state Board of Education, whose members are appointed by the governor with advice and consent of the state Senate.

That same article places the responsibility of the West Virginia Legislature to provide, through the passage of laws, for “a thorough and efficient system of free schools,” and requires the state board to “perform such duties as may be prescribed by law.”

The laws governing the regulation and funding for public schools can be found in State Code chapters 18 and 18A, with new laws passed by the Legislature updating those code chapters every year.

“I find it ironic that today the board members received their new copies of the West Virginia Code,” Hardesty said. “This is the West Virginia law book that governs public education. We all got a shiny new copy today.”

Hardesty held up the book containing the state’s education laws, a nearly 1,350-page book, as well as the green books which include updates to the education laws passed over the last five years.

“There is a real misconception amongst the voters and the general public in the State of West

Virginia of what that book actually is and who the actual author of that book is,” Hardesty said. “Ladies and gentlemen, I assure you the author of that book is not the West Virginia Board of Education nor the West Virginia Department of Education. This is a book of school law created by legislators past, present, and hopefully in the future right across the way.”

In comparison, Hardesty held up one sheet of paper that included the entirety of the State Code regulating the state’s small and growing public charter schools and statewide virtual charter school system. West Virginia’s public charter school pilot program was created in 2019 by the Legislature and updated in 2021. There are now two statewide virtual charters and five physical charter schools serving students in the Eastern Panhandle, Monongalia/Preston counties, Harrison County, and Kanawha County.

Next, Hardesty held up a notecard that contained the number of laws and regulations governing home school students, some of whom receive the Hope Scholarship, an educational voucher program that allows parents to use the equivalent of their per-pupil school aid formula state expenditure – up to $5,267 per student for the 2025-26 school year – for private school and home school expenses.

Hardesty stressed that he was not opposed to West Virginia families exercising their right to school choice. But while regulations on home schooling and public charter schools remain minimal, teachers and school administrators in all 55-county school systems remain handcuffed by the overregulation of public education which governs the day-to-day workflow of teachers and controls staffing decisions and funding formulas.

“The Legislature has made a lot of changes to this book to incorporate the school choice model. They’ve made no changes to the funding cycle. They’ve made no changes to Chapter 18A, which causes a public school system to have to operate like a business but operate like a business without the ability to effectively manage their workforce. No changes made there,” Hardesty said.

The state Department of Education will receive the official October public school enrollment numbers in the coming days, which are expected to be down from the previous school year enrollment number of 241,024 students – down by more than 4,000 students from the 2023-24 school year. That’s down by nearly 40,000 students from October 2014 enrollment numbers.

The October enrollment number determines how much county school systems receive in state school aid formula funding. County school systems also rely on property taxes, bonds and levies. West Virginia’s enrollment slide has been decades in the making but driven in part in recent years to the state’s new open enrollment program, public school students leaving to take advantage of the Hope Scholarship, and statewide virtual charter school enrollment.

Decreases in public school enrollment has caused county boards of education to make hard choices in order to remain solvent, including closing and consolidating schools, and laying off teachers and school service personnel.

Hardesty – a long-time lobbyist and former Democratic state senator – said the focus by the Republican-led Legislature on school choice since the 2018 teacher strikes is an effort by some business groups, such as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), to purposely bankrupt public school systems.

“You’ve got to remember; this is the business community that’s come together to create this playbook. And they feel like the only way that they can accomplish what they want to do is to decimate public education,” Hardesty said. “And how do you do that? You do it financially. If you bankrupt the school system, change can occur.”

The State Treasurer’s Office which manages the Hope Scholarship program estimates that that program will cost the state $244.6 million during the 2026-27 school year. The cost of the Hope Scholarship for the current fiscal year is $110 million, up from $45 million in the previous fiscal year.

“The cost has grown exponentially out of control, and members of the Legislature have privately told me that this has gotten too big too fast, and we can’t control it. But they have no remedy,” Hardesty said.

Hardesty also said that the exodus of students from the public school system is leaving students with the most severe learning challenges while leaving school systems with fewer dollars to address those challenges.

“What else has Hope done? What Hope has done, it’s taken our best and brightest and gives them other opportunities to go somewhere and seek other forms of education,” Hardesty said. “Again, that’s fair. But what has it left us…the toughest to try to educate. We’ll take that challenge head-on, but it’s hard, and it’s very expensive to provide the services for those children.”

Hardesty called on the Legislature to take a hard look at reducing the number of laws and regulations that make it harder for teachers to do their jobs, and reform the state school aid formula to address the challenges facing county school systems.

“Ladies and gentlemen, you tell me, are the options fair and equitable? Which one is designed to fail and which one is not,” Hardesty said. “Now Legislature, I don’t expect to get Christmas cards from any of you and that’s fine. If you all want to seek a solution, I’ll be a willing partner. This board will be a willing partner. This department will be a willing partner. But I’m going to tell you now, if you’re not willing to get into the school aid formula and chapter 18a, don’t waste my time and don’t waste your time.”